Mouse Models of Cancer: Weight Loss, Endpoints and Nutritional Support

As much value as computational science or in vitro experiments can bring to research, many questions in oncology can only be answered by in vivo studies in complex living organisms. Mice and rats have been models of choice for a long time, and even more since the development of genetically engineered models (GEMs). However, to stay in alignment with the 3R principles (Replace, Reduce, Refine) (1), which provide a framework for performing more humane animal research, it is our legal and ethical obligation as researchers, veterinarians and animal caretakers to use methods which minimize animal suffering and improve their health and welfare.

In oncology especially, animals with tumors may experience weight loss, distress or pain, and special care and attention need to be given to their health and welfare. In this article, we will discuss the different types of mouse models used in oncology, the humane endpoints to set up before any experiment in those models, and how to support your animals’ wellbeing with ClearH2O gels.

Mouse Models in Cancer Research

There are broadly two categories of mouse models that can be used in oncology research (2): Xenograft models and GEMs. In our previous blog, we described the three types of models to be used for xenografts (immunocompromised, humanized and PDX). However, those models can have some limitations: many of those studies use immunocompromised mice, with a subcutaneous implantation of the tumor tissue, which prevent immune responses and site specific interactions (3), thereby losing crucial features of the tumor microenvironment.

Genetic manipulation in mice can help study tumor initiation, maintenance, progression and response to treatments. Two of the main types of genes that play a role in cancer are oncogenes (genes that help cells grow) and tumor suppressor genes (genes that slow down cell division, repair DNA mistakes, or are involved in apoptosis) (4). As you can imagine, when those genes work too much or not enough, respectively, the cells can grow out of control and lead to cancer.

Below are the most commonly used GEMs for oncology research:

- Transgenic mice are mice in which DNA from an unrelated organism has been artificially introduced (most often from human) to induce its expression.

- Gene targeting technology allows the introduction of specific mutations in specific genes. This can result either in the deletion (knockout) or the insertion (knockin) of specific sequences in the genome. These mutations can mimic those that are often found in human tumors.

- Conditional or inducible models rely on the induction of chosen mutations in a tissue-specific or time-specific manner. The most common conditional systems used are Cre-loxP or Tet-On/Tet-Off, using exogenous ligands such as doxycycline and tamoxifen. To learn more on the cre-lox system, see our blog: Tamoxifen Delivery: Say No to Gavage and Repeated Injections

- Large chromosomal abnormalities, such as deletions, duplications, inversions and translocations of full fragments of chromosomes, can lead to fusion genes (5).

Humane Endpoints in Oncology

Oncology is one of the biomedical research fields where animals will experience the most distress and pain (6). Endpoints are defined as the points at which an experimental animal’s pain or distress is terminated, either by humanely euthanizing the animal, ending the experimental procedures or providing treatment (7). Those endpoints should be part of a consultation process between the researcher and the veterinarian to ensure the animals’ wellbeing while still meeting the research objectives (8), and be clearly defined in any study protocol submitted to the IACUC (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee) for review (9).

Standard endpoints can be based on the indicators below, and used to develop a scoring system:

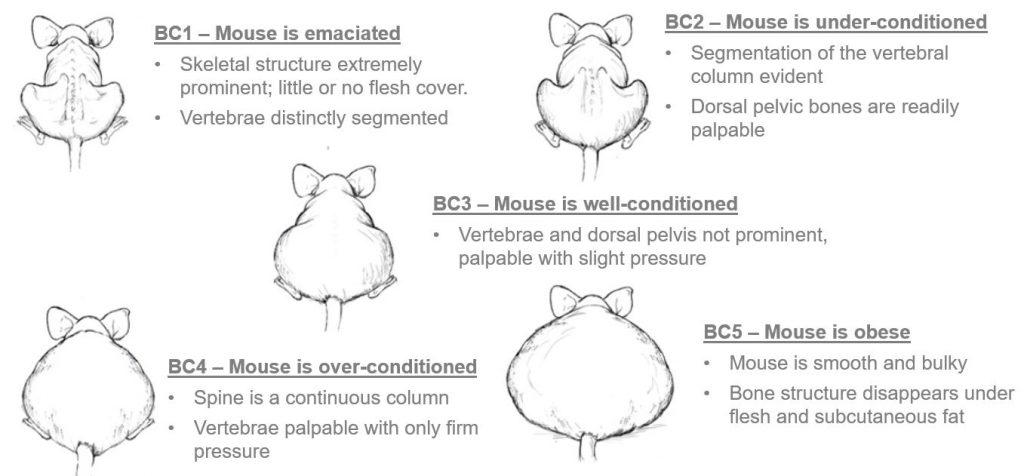

- Health and nutritional status assessment: dehydration signs, body weight and Body Condition Scoring (see BCS sheet below(10)) are routinely used to monitor the animals’ welfare. A loss of 20% body weight is typically used as a default endpoint. However, in cancer models, these can be difficult to ascertain accurately because an increase in tumor mass can mask the loss of overall body weight (11). For more on dehydration, see our pervious blog article: Leading Causes of Dehydration in Laboratory Animals

- Behavioral changes: observation and measurement of activity level, behavior (grooming, nesting), vocalization, aggression, or response to handling, while subjective, can be incorporated in the scoring system.

- Fur and skin appearance: sunken eyes, hunched posture, piloerection or skin ulcers are all clinical signs of distress.

- Pain evaluation: the grimace scale is a published method to assess pain in different species. For more information, read our previous blog: Understanding the Grimace Scale as a Pain Assessment for Laboratory Animals

Additional endpoints specific to cancer models (such as tumor size, tumor ulceration, ability to ambulate) or specific to the known pathology of the particular model used, can also be taken into account (12, 13).

Weight Loss in Cancer Mouse Models

Unexplained weight loss is often one of the first noticeable symptoms of cancers. As the disease advances, wasting and muscle loss, also called cachexia, can become more severe and contribute to mortality. In particular, the increased production of cytokines and other pro-inflammatory molecules secreted by the immune system to inhibit tumor development and progression can also unfortunately culminate in skeletal muscle wasting.

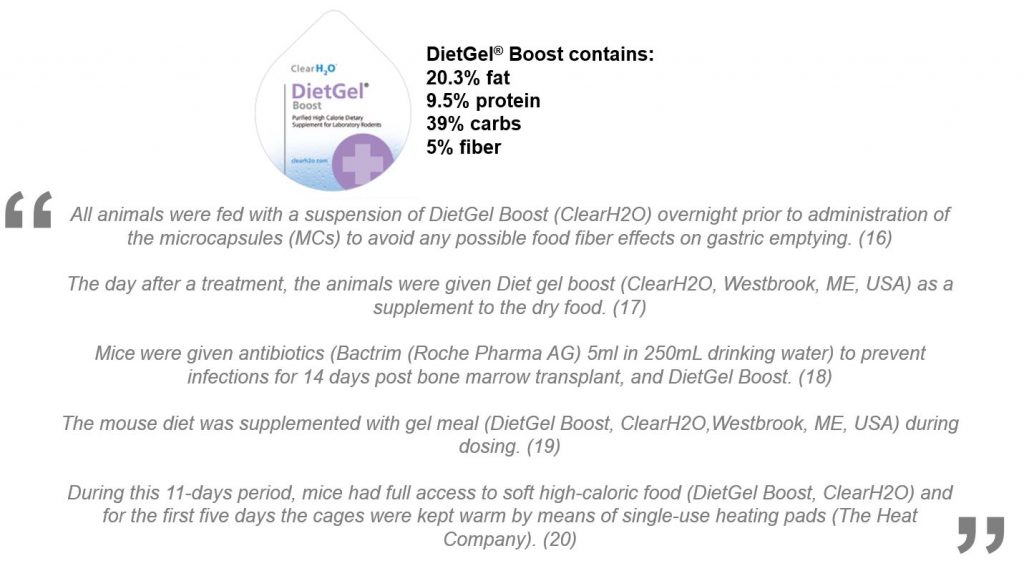

DietGel® Boost, ClearH2O’s high-energy nutritional supplement for rodents, is used extensively in oncology research, to support the health of weak and debilitated animals, dealing with weight loss. Made with peanut butter and with a soft texture, its great taste promotes consumption and provides supplemental caloric and nutritional intake. You can find below a handful of selected quotes on DietGel® Boost usage for mouse models of cancer.

References:

(1) The 3Rs – NC3Rs

(2) Maximizing mouse cancer models – Frese & Tuveson, 2007

(3) Mouse models for cancer research – Zhang et al., 2011

(4) Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes

(5) Fusion genes in solid tumors: an emerging target for cancer diagnosis and treatment

(6) Humane Endpoints

(7) Canadian Council on Animal Care

(8) Humane Endpoints for Laboratory Animals – UCDavis

(9) Endpoint Guidelines – Emory University

(10) Health Evaluation of Experimental Laboratory Mice

(11) Endpoints for Mouse Abdominal Tumor Models: Refinement of Current Criteria

(12) Guidelines for the welfare and use of animals in cancer research

(13) Humane intervention points for rodent cancer models – McGill

(14) Pancreatic Cancer-Induced Cachexia and Relevant Mouse Models

(15) A novel transplantable model of lung cancer-associated tissue loss and disrupted muscle regeneration

DietGel Boost® use in Cancer:

(16) The in vivo fate of nanoparticles and nanoparticle-loaded microcapsules after oral administration in mice: Evaluation of their potential for colon-specific delivery

(17) Ultrasound Improves the Delivery and Therapeutic Effect of Nanoparticle-Stabilized Microbubbles in Breast Cancer Xenografts

(18) A conditional inducible JAK2V617F transgenic mouse model reveals myeloproliferative disease that is reversible upon switching off transgene expression

(19) Identification of Eph receptor signaling as a regulator of autophagy and a therapeutic target in colorectal carcinoma

(20) Towards more accurate preclinical glioblastoma modelling: reverse translation of clinical standard of care in a glioblastoma mouse model.